Note: This blog post was originally written for and published by the Castle Studies Trust. See the original link below.

Bethany Watrous of Experience Heritage examines how her digital reconstruction of the Jacobean manor house at Slingsby Castle sheds light on its original form when first built in the C13.

The ruins of Slingsby Castle, Yorkshire

The mysterious Slingsby Castle in Slingsby Village, North Yorkshire, is a ruin of a 17th century manor built on the site of a 13th century moated castle which survived, at least in part, into the early 17th century. The manor was built for Sir Charles Cavendish II, grandson of infamous Bess of Hardwick, by John Smithson. An earlier design for a manor on the same location was created for Sir Charles Cavendish I by Robert Smythson, father to John (who changed the spelling of the family name). Original architectural sketches for both versions of the manor still exist in the Royal Institute of British Architects’ Smythson Collection.

It was with this evidence, as well as further historical record, that I set about reconstructing both versions of the manor in digital 3D. The intention of this project was multifaceted. The ruins of Slingsby Castle have long been left to decay and the local community was in discussion about whether to put funding into refurbishing the site or allowing it to continue to be reclaimed by nature. Interactive digital models would help to engage the public in the conversation. However, the digital reconstruction would also provide further research about a site with a greatly confused historical record. It would help to tell a story about a significant phase of British architecture and give better insight into the original medieval castle.

The little we know about the original medieval castle comes from historical writings and archival material. A royal license was granted in 1216 for a manor or castle on a site owned by the Wyvilles. It was sold to Ralph de Hastings in 1344 and in the same year, a license was sought to crenellate a structure there1. In 1475 William Lord Hastings was granted permission to “build, enclose, crenellate, embattle and machiociolate”2 and it’s believed that this was the time of the creation of the moat. In 1619, the historian Dodsworth visited the site and described seeing the Hastings’ crest over the gates and a “church within the castle walls”3. The Jacobean manor was likely built on the site soon after Dodsworth’s visit.

There are many theories as to whether the Jacobean manor reused original parts of the castle. The site has not been inspected by modern archaeologists and we were not able to gain access for the purpose of this study. Modern historians disagree on the topic. Some believe no part (including the moat) of the Jacobean manor is medieval, while others have found evidence suggesting otherwise.

3D model of Jacobean manor, by Experience Heritage

19th century historians described what then still remained of the 17th century manor including a wall running along the inside of the moat and “turrets at each angle”4 which some believed to be remains of the medieval bailey walls3 or following the original footprint. Another theory suggests that the original structure was either incorporated in or influenced the development of the basement vaults. On multiple floor plans, attention has been drawn to the irregular nature of the northwest room’s west wall.

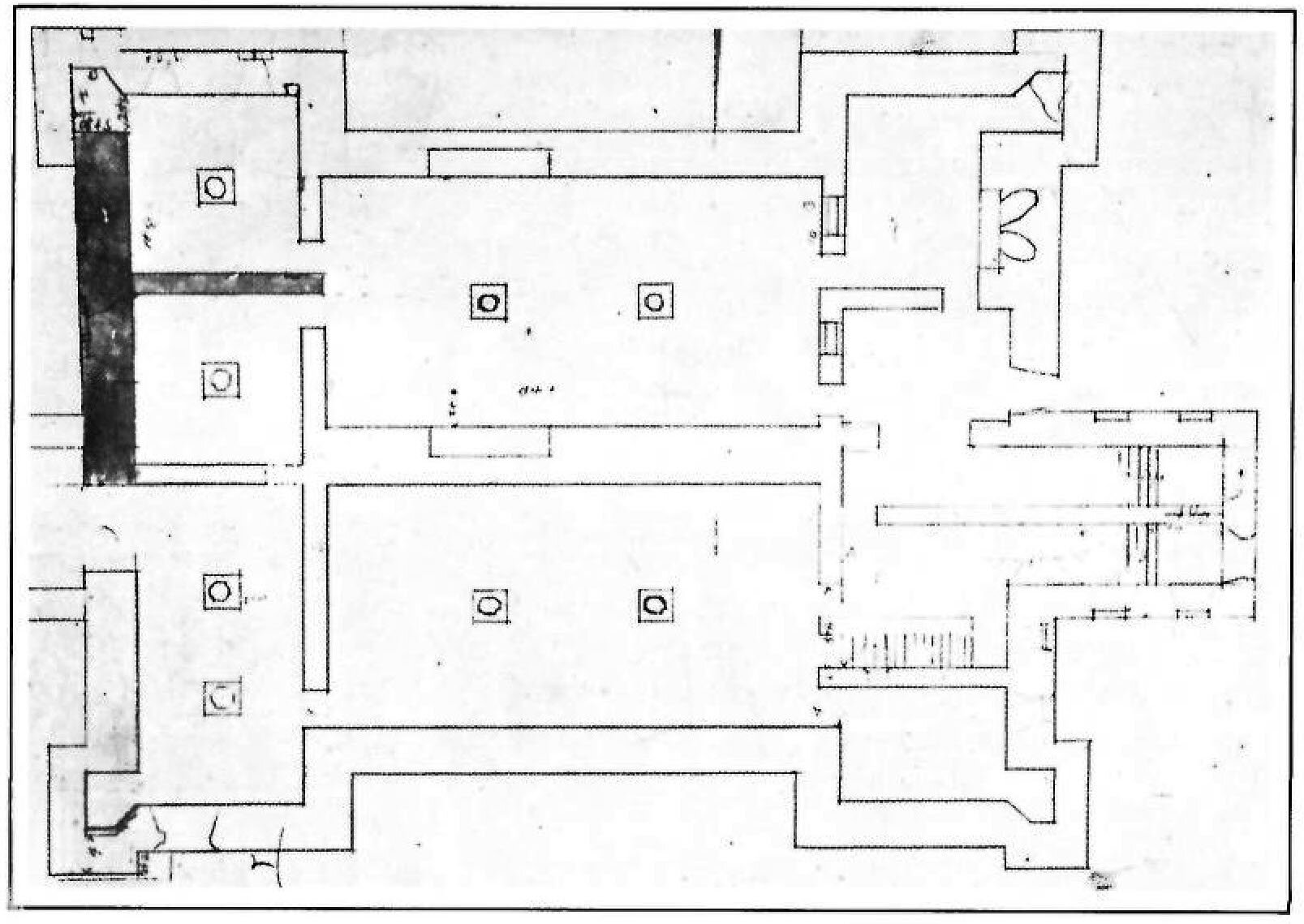

1700 plan of the Jacobean design, highlighting the northwest wall ©Hovingham Hall Estate

The earlier, Elizabethan floor plan may give us insight into another piece of the medieval castle. The plan contains all the symmetrical balance of a typical Elizabethan design except for the off-center placement of its gatehouse. During the digital recreation and movement through the 3D model of this plan, the sharp curve of the path from gatehouse to main house was too jarring to ignore. Furthermore, when studying the plan, it became apparent that the manor’s only gatehouse was not meant to be the main entrance. On the opposite side, the main entrance leads over a stepped bridge to a raised terrace, whereas the door into the manor from the garden is hidden to the side of the portico. This suggests that the gate’s real purpose was as a reused medieval ornament for exhibition during progression around the estate. Therefore, Smythson’s floor plan may capture the outline of one part of the original castle.

View of the off-centre gatehouse as part of the 3D model of the Elizabethan design, by Experience Heritage

Bethany Watrous is the director of Experience Heritage which combines her archaeological and digital backgrounds to create engaging, authentic and interactive digital displays, 3D models, film and mobile apps for the heritage sector. Learn more at www.experience-heritage.com.

Featured image copyright of All Sainst Slingsby